The Alta conflict was a political dispute that lasted from 1968 to 1982. Sami interests and environmental protection interests fought against a large hydropower development in the Alta River. In many ways, the case became a turning point for Norwegian Sami policy and for consideration for nature and the environment.

In 2023, the film “Let the river flow” came out with artist and actress Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen in the lead role. The film is based on real events from the Alta conflict and shows how activists fought for both nature and Sami rights.

This is how it went

In 1968, the first plans for the development of the Alta-Kautokeino watercourse were put forward. This was met with harsh criticism and five years later the “Alta Committee” for the conservation of the watercourse was formed.

What made the case extra special compared to other development cases that took place at the same time was that any development would have very negative consequences for Sami reindeer husbandry. Among other things, it was proposed to dam the Sami village of Masi. This was eventually excluded from the plans and in 1983 the village was permanently protected.

The environmental activists were particularly concerned with the Altaelva as a salmon river, agriculture and the climate in the Alta area and distinctive natural qualities in the Altadalen.

In the summer of 1979, the interests were gathered in the organization Folkekaksionen against the development of the Alta/Kautokeino watercourse. These organizations collected 15,000 signatures which were sent to the Storting (Norwegian Parliament). Nevertheless, it was decided to build a dam.

The hunger strike outside the Storting

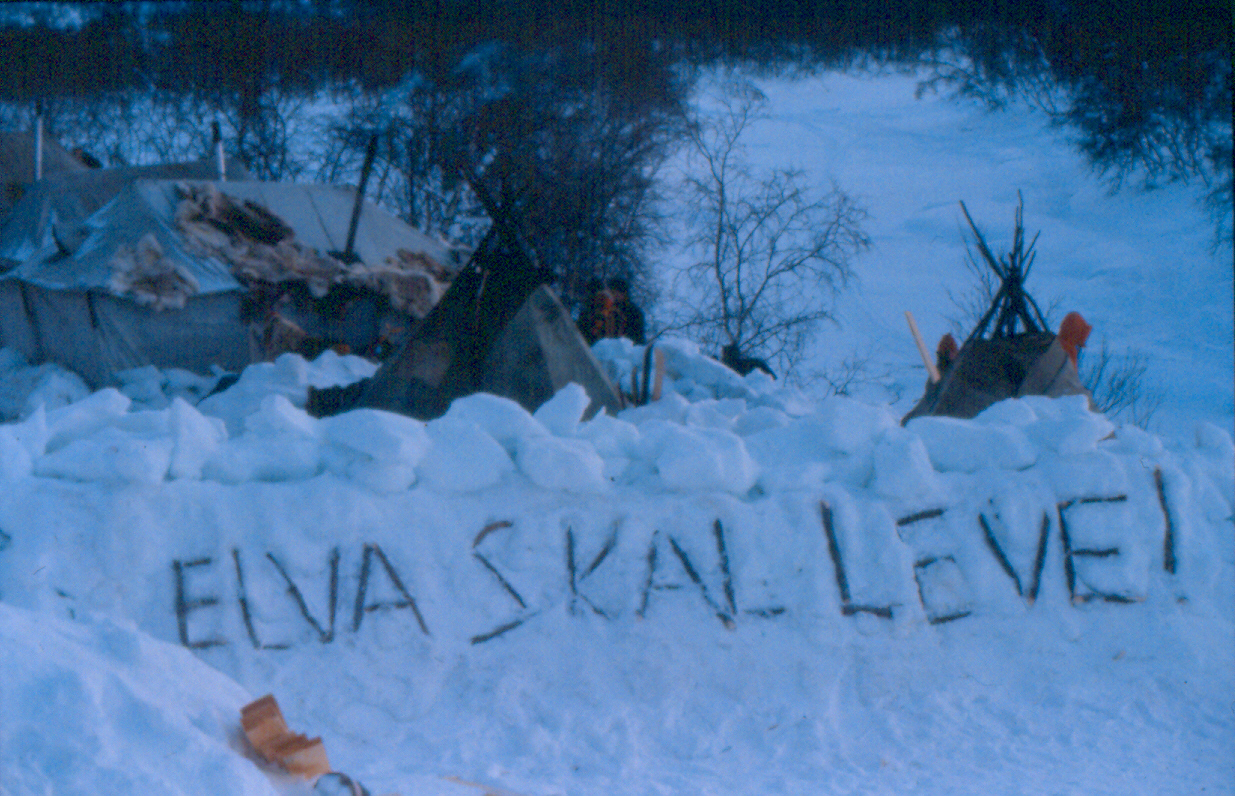

This summer civil disobedience was used by the people’s action, which halted construction work for a period. In October of the same year, a group of Sámi set up tents and lavvo outside the Storting in Oslo and demanded that the development be halted. The government said no and the Sami responded with a hunger strike for a week. One of the hunger strikers was Mathis Hætta, who performed the joik Sámiid ædnan, which in 1980 was the chorus in the Norwegian entry in the Eurovision Song Contest.

In 1980, a judgment was handed down in the Alta Herredsrett, which was critical of large parts of the proceedings. The development was, among other things, in breach of the conservation decision by Masi, but the development itself was legal. This led to construction work starting up again in January 1981. The popular action was in place with new civil disobedience actions, which were stopped by the police. In February 1981, construction work was stopped again to assess whether the work might be in breach of the Cultural Heritage Act. The questions were clarified and construction work resumed in September 1981.

The result of the conflict

In 1982, the case was put to an end, when the Supreme Court declared that it agreed with the Alta Herredsrett that the development was legal and the popular action was dissolved the same year.

In 1987, the Alta power plant was put into operation. More than ten years of protests and resistance failed to prevent the expansion of the waterway. In contrast to the environmental activists, the Sami experienced a great victory nevertheless. The Alta case was a turning point in the history of the Sami people. All the attention the case received contributed to many Sami feeling safer and more accepted as people. The case also had great significance for the development of Norwegian Sami policy. Among other things, the case led to the Sami Parliament being established and opened in 1989.

The 110 meter high dam in Sautso was the last major power development in Norway.